Wenatchee Mural Painter Was Resilient – 05/16/2024

Written by Chris Rader

For decades, Wenatchee Valley Museum members and visitors have admired the colorful 18’x7’ mural at the south end of the museum lobby. Many are aware that it was painted by Peggy Strong in the 1930s as part of the Roosevelt Administration’s public works initiative to create jobs for artists during the Great Depression. But few know of Strong’s remarkable life, including the many challenges she overcame on her path to becoming a famous Northwest artist.

Early life

Peggy Strong was born in Aberdeen, Washington in 1912 to a civil engineer father and a mother active in progressive politics. Just as she was beginning to walk, it was discovered that Peggy had been born with faulty hip sockets. “She was operated on and had to lie on her back with legs in casts splayed at right angles to her body, and slowly brought back to a normal position,” her younger sister Jean said in a documentary she produced about Peggy. “Quite a challenge for a two-year-old!”

Peggy and her four siblings grew up in Tacoma in a well-heeled neighborhood. Their father built roads and railways for timber companies, and the family often spent summers in the woods at his construction camps. Living so close to nature, they all learned to love and revere it.

Despite her bad hips, as a teen Peggy loved to ride horseback – riding after the hounds on flat, open fields around Tacoma. She also loved to draw, with horses a frequent early subject. Her artistic talent caused her parents to send here to the Annie Wright Seminary, where she received intensive instruction in art. She then attended the University of Washington as an art major. “She certainly could create abstract art, but found more satisfaction in figurative painting and portraiture,” sister Jean Walkinshaw stated. “She also found she could make money painting her friends and acquaintances – so at the age of 20 she had saved enough money to go to art school in Paris.”

Peggy was headed for the East Coast to board a ship for France, in a car driven by her boyfriend, when calamity struck. The car had jumbo tires that were advertised as being blowout-proof, but in Wyoming one of the tires blew out. The car careened out of control, rolling over and over, and Peggy’s spine was severed.

Her mother took her to Detroit for surgery; there, for the second time in her life, Peggy had to lie quietly on her back for days. To pass the long hours she carved figures in soap, but as she held them overhead the shavings sometimes fell into her eyes. This must have been frustrating as well as painful!

Despite medical treatment, Peggy Strong never again had feeling below her armpits. She sued the tire company, and won, but that did not cure her paralysis.

“She would not be daunted, however,” Walkinshaw said. “She learned to drive a car with her hands. She even pursued her love of the hunt, but now she was bouncing across the Tacoma prairies in her convertible rather than on the back of a horse.”

Painting remained her main passion. She studied privately with noted artists Mark Tobey, Sarkis Sarkisian and Frederick Taubes and continued to paint portraits on commission. Taubes taught her to grind her own paints from raw pigments and to mix her own varnishes.

Receives recognition

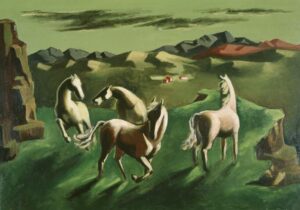

Peggy Strong’s first brush with fame came in 1936 when she won first place in the Seattle Art Museum’s annual show with a painting of a ring of horses on a bluff, titled “Mountain Merry-go-round.” The show’s curator wrote, “Miss Strong displays a high degree of skill because she can handle any subject with equal ease, painting it with surety and directness with swinging brush strokes.”1 Strong was a figurative painter, though, and the Seattle Art Museum was focusing more and more on abstract art – so her award-winning painting was relegated to the basement for decades.

Courtesy of the Seattle Art Museum. “Mountain Merry-go-round,” painted in vibrant greens, is in the collection of the Seattle Art Museum.

In 1938 her “Woman in Green” was chosen to represent Washington state in the National Exhibition of American Art at the Rockefeller Center in New York. The following year Strong was included as one of 60 women artists in the Golden Gate International Exhibition at the San Francisco’s World’s Fair.2 She also had paintings exhibited at art museum shows in Tacoma, Seattle, Portland, Memphis, Cincinnati and Richmond, Virginia.3

Later that year she won a competition to paint a mural in the Wenatchee post office. Hers was one of 1,371 murals commissioned throughout the United States to decorate federal buildings with high-quality work while providing employment for artists during and after the Depression.4

Strong described the project as follows:

The mural design was the winner in a competition conducted by the Section of Fine Arts, Public Buildings Administration, Federal Works Agency, Washington, D.C. It was anonymously judged among 46 entries by a jury at the Seattle Art Museum and again by a jury in Washington, D.C. The title of the mural is “The Saga of Wenatchee.” It has been painted in oil, on canvas, and will be cemented in place on the south wall of the post office lobby…. The main panels are approximately 18 feet wide and seven feet high. The subject matter of these panels is Wenatchee, past and present, with a central theme of postal service. The four small panels depict local industries.5

The post office, which is now the home of the Wenatchee Valley Museum and Cultural Center, had a wall for the mural that was a bit complicated. Strong had the challenge of working around a doorway and two bulletin boards to create an integral design. With a theme of postal service past and present in Eastern Washington, it shows orchard workers, farm animals, a forest, a homestead, a stagecoach carrying mail and a farm couple looking in their mailbox. A sculptured rock pattern draws the whole design together. The mural is an example of the Regionalist art movement, capturing the ambience of various areas of the U.S.; its slightly elongated figures show the influence of Regionalism leader Thomas Hart Benton.6

Being confined to a wheelchair, Strong had never before undertaken such a large project. With her engineer father’s help, she cut and fitted the six-panel canvas to the wall of her home studio in Tacoma. Her father built her a platform with a pulley and chain from which to work. When finished, the colorful mural was displayed at the Seattle Art Museum before being installed in Wenatchee – where it was received with delight. Strong received $2,600 for the work. “The Saga of Wenatchee” has been accessioned to the National Collection of Fine Arts at the Smithsonian Institution, and is listed on the National Register of Historic Sites. It is on permanent loan to the Wenatchee Valley Museum.

In her documentary, Jean Walkenshaw said that during World War II, her sister was commissioned to paint murals “to cheer the troops. One was of Paul Bunyan and his blue ox, (in the Troops in Transit lounge) in the Tacoma Union railroad station, and the other in the (Alaskan military base) Dutch Harbor officers’ club. When the Tacoma station was renovated, the Paul Bunyan mural was moved to a safe haven at the student union building at the University of Puget Sound. But I don’t know what happened to the mural that was at Dutch Harbor.”

Spent time in Oregon, New York, Europe and California

Peggy Strong not only drove a car that her father had adapted for hand control, but often pulled a large house trailer behind it. She moved to Oregon with a helper and often camped in the trailer. Her sister said she also drove her car to New York, painting portraits along the way. In New York she became a member of Portraits Incorporated – and her paintings continued to win awards and be displayed at museum shows across the country. Her “April Transplant” won a competition sponsored by the Junior League and was featured on the front cover of their national magazine.

“Peggy was determined to walk again,” Walkenshaw said. “She was fitted with braces, saying they would straighten her legs, and would pull herself up against the car door. My father was there to encourage her, but she toppled easily. She went East to the best surgeons and even tried England and a faith healer there who, at a large public meeting, became livid with her because she could not get up and walk when he commanded her to do so.”

Walkenshaw speculated that it was her trip to Europe that brought forth a darker, sometimes surrealistic style in Peggy’s later paintings. She said her sister gave up hope of walking or getting married, and had moments of depression interspersed with intense religious seeking.

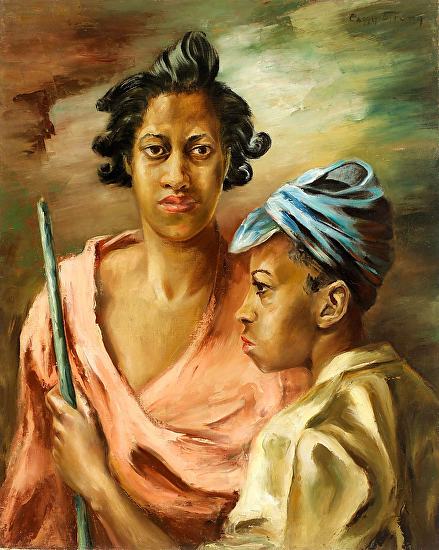

Source: cascadiaartmuseum.org. “Untitled (Woman with Shackles)” was exhibited at the Cascadia Art Museum in 2016-17. The untitled oil represents some of Strong’s darker work, toward the end of her career.

In the late 1940s Strong moved to San Francisco and rented an apartment on Telegraph Hill. Her paintings sold well and the press loved her. “She was doing fine living alone with a helper coming in during the day,” Walkenshaw said. “But it was here that she had another very troubling experience. The young woman helping Peggy lost her mind, and threatened Peggy with a butcher knife. Fortunately, a friend of Peggy’s dropped by and rescued her. The young woman escaped and was later found nearby, dancing naked in the street.”

In California Peggy Strong met the well-known Black theologian Howard Thurman. Named by Life Magazine as one of the 12 great preachers of the 20th century, Thurman was an important mentor to Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. “Peggy was probing deeply into life issues and took copious notes on the varied philosophical, spiritual and psychological books she read,” Walkenshaw said. “Thurman visited her once a week and they had challenging discussions on these topics.”

Thurman was founder of the Fellowship Church, which Strong attended. “His emphasis on those who were suffering or marginalized in society spoke to Peggy and she became close friends with him…. She gave him painting lessons, and he gave her a solo exhibition at his church.”7 In his autobiography, Thurman called Strong “a superbly gifted artist and portrait painter” and “one of the most resourceful people I have ever known.”8

Peggy Strong died of liver disease in June 1956, at her brother’s home in Eugene, Oregon. She was just 44 years old.

Critical acclaim

Sixty years after her death, Strong was revived in the public eye in a retrospective exhibit at the Cascadia Art Museum in Everett from September 2016 through January 2017. The exhibit, called “A Spirit Unbound,” included many of her portraits as well as “powerful works that display a sensitivity to social issues,” according to curator David Martin. He added, “The paintings completed in her final years before succumbing to kidney disease frequently conveyed a feeling of despair and hopelessness.”9

Seattle Times art critic Michael Upchurch panned some of Strong’s portraits as sentimental but praised several of the more complex works.

When she looks inward, communicating in a symbolist shorthand, her work comes alive. Its lines grow sharper; its colors take strange and challenging turns. In “Hate,” a dozen blood-red figures crouch in a ritual circle, as if about to pounce on an unseen target. It’s a hellish, ferocious vision. “Rain” initially seems its opposite, but the way its gray silhouetted figures are dissolving under streaky raindrop translucence suggests a similar collective fate or doom.10

Art blogger Nana Carrillo summed up Strong’s style in these words. “Her paintings show the influence of the German Expressionist painters of the 1920s. In her lifetime, she mastered two art styles – abstract expressionism and stylized realism which she used for portraiture.”11

Peggy’s sister Jean, who was a longtime television producer based in Seattle (producing content for the History Channel, KING-TV and KCTS), created a 20-minute video about her famous sibling that ran throughout the Cascadia exhibition. It can be viewed here.

The staff, board and members of the Wenatchee Valley Museum and Cultural Center are continually grateful that “The Saga of Wenatchee” keeps Peggy Strong’s memory alive in our facility.

ENDNOTES

- “Peggy Strong, Remembered by Her Sister Jean Walkinshaw,” documentary, Seattle Colleges Cable Television, September 2016.

- “The Artwork of Peggy Strong,” tacomahistorylive.com, May 7, 2017.

- “Mural Unveiling Saturday,” The Wenatchee Daily World, Oct. 3, 1940.

- “The Saga of Wenatchee,” Barbara Corey, North Central Washington Museum brochure.

- Daily World, op. cit.

- Corey, op. cit.

- Nana Carrillo, “Peggy Strong, Tacoma Artist of the Early 20th Century,” blog post April 3, 2017.

- Walkenshaw, op. cit.

- Gale Fiege, “Edmonds museum showcases artist whose life was cut short,” HeraldNet, Sept. 9, 2016.

- Michael Upchurch, “Peggy Strong retrospective raises more questions than it answers about her career,” Seattle Times, Oct. 25, 2016.

- Carrillo, op. cit.

This story was originally published in Confluence Magazine in the Spring edition of 2024. In an effort to preserve these stories, the Wenatchee Valley Museum and Cultural Center will be posting these stories on the museum’s official blog.

Become a member to get a free copy of Confluence Magazine. Learn more about how to become a member here!